Wanted: Volunteers for immediate overseas assignment. Knowledge of French or another European language preferred; Willingness and ability to qualify as a parachutist necessary; Likelihood of a dangerous mission guaranteed.

American servicemen training for deployment in the months leading up to D-Day were given this offer over loudspeakers at military bases across the nation. Knowing nothing else, a few brave men (women were not being recruited for this specific operation) volunteered for a mysterious assignment knowing no other details. It wasn’t until later, after a battery of physical and psychological tests, that these young men would travel to our nation’s capital and discover they were to become commandos in an organization most Americans didn’t even know existed. They were to become OSS Jedburghs.

“Surprise, kill, and vanish.”

– Motto of the Jedburgh teams

Operation JEDBURGH:

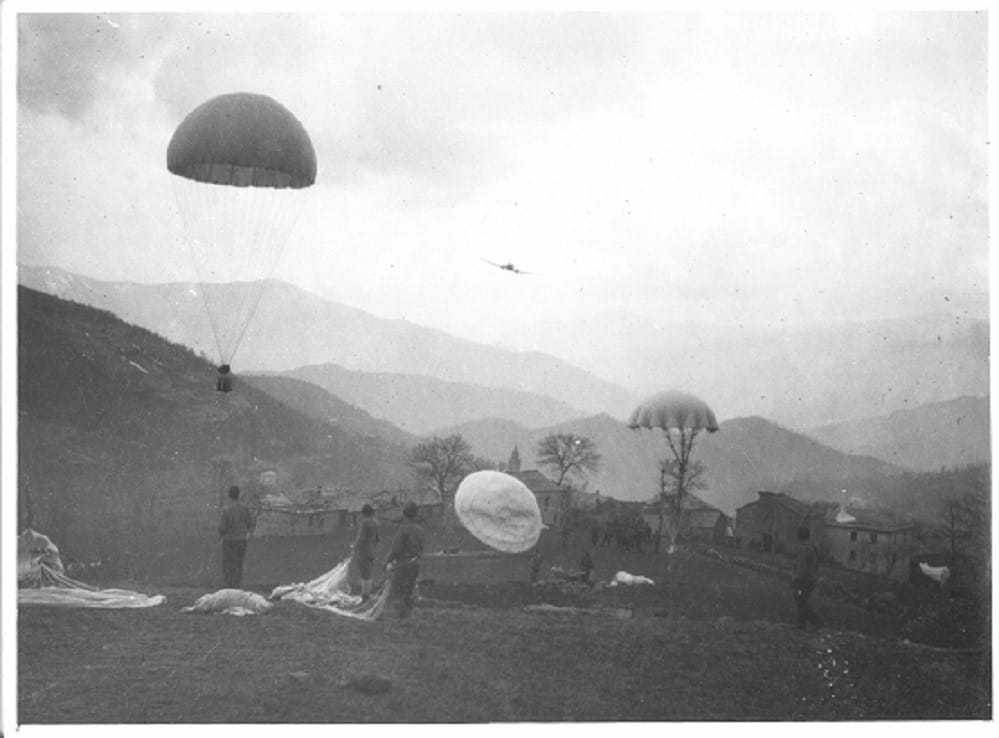

Parachuting behind enemy lines in the cover of night, the Office of Strategic Services’ (OSS) elite Jedburgh teams were special operations paratroopers sent into Nazi-occupied France, Belgium, and the Netherlands to coordinate airdrops of arms and supplies, guide local partisans on hit-and-run attacks and sabotage, and assist the advancing Allied armies to defeat the Third Reich.

The Special Operations (SO) branch of OSS ran guerrilla campaigns throughout Europe and Asia during World War II. As with many other aspects of OSS’s work, the organization and doctrine of the branch was guided by British experiences in the growing field of “psychological warfare.”

British strategists in the year between the fall of France in 1940 and Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941 wondered how Britain—which then lacked the strength to force a landing on mainland Europe—could weaken the Reich and ultimately defeat Hitler.

London chose a three-part strategy to utilize the only means at hand: naval blockade, sustained aerial bombing, and “subversion” of Nazi rule in the occupied nations. A civilian body, the British Special Operations Executive (SOE), took command of the latter mission and began planning to carry out Prime Minister Winston Churchill’s charge to “set Europe ablaze.”

This emphasis on guerrilla warfare and sabotage fit with OSS Chief “Wild Bill” Donovan’s vision of an in-depth offensive against the Nazis, in which saboteurs, guerrillas, commandos, and agents behind enemy lines would support the Allied armies’ advances. OSS seemed the natural partner for SOE in combined planning and operations when the United States decided in 1942 that America would join Britain in the business of “subversion.”

Together, OSS’s SO branch and Britain’s SOE created the famous Jedburgh teams that parachuted into France to support the Normandy landings.

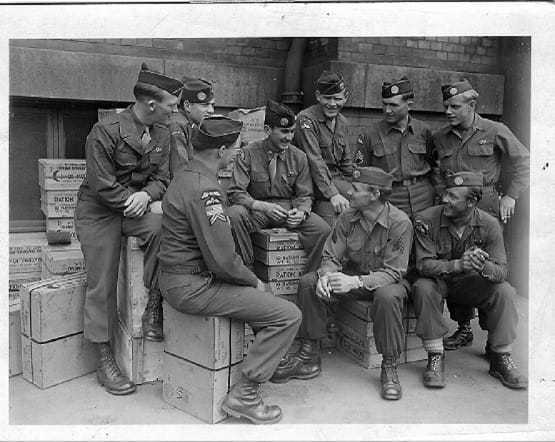

A “Jed” team consisted of two to four men: some combination of an American OSS officer, a British officer, a Free French officer or enlisted man, and sometimes a Belgian, Dutch, or Canadian soldier. One member of each team was always a radio operator. The US commandos on these small teams purposely fought in uniform with no obvious connection to OSS to decrease the likelihood they would be shot as spies if captured.

The teams received extensive foreign language instruction, as well as training in parachuting, amphibious operations, skiing, mountain climbing, radio operations, Morse code, small arms, navigation, hand-to-hand combat, explosives, and espionage tactics. Each Jedburgh team carried a communications radio, commonly referred to as a “Jed Set,” which was critical for communicating with Special Forces Headquarters in London.

OSS Operational Groups—larger uniformed units akin to Army Rangers—fought in France, Italy, Greece, Yugoslavia, Burma, Malaya, and China, usually alongside partisan forces. The Jedburghs, however, mainly fought in Nazi-occupied France, joining with the French resistance (Maquis) against the German occupiers. The first Operation JEDBURGH team was deployed the night before D-Day.

More than 90 Jedburgh teams parachuted into France in 1944, coordinating airdrops of arms and supplies and conducting hit-and-run attacks and sabotage raids on German forces. Many teams had to parachute in blind because communication from behind enemy lines was sparse—an extremely dangerous situation for any parachutist. Once in, they would meet up with the Maquis or other local resistance groups, providing an essential link between the guerrillas and the Allied command.

Legend of the Jedburghs

How Operation JEDBURGH got its name is still somewhat of a mystery. Some say it was inspired by the name of a South African town where Boers used guerrilla tactics against the British. Others claim it was based upon the name of the radio sets the teams used (Jed Sets). Still another theory states that the code name was chosen to correspond to J-Jour, the French translation of the US military term, D-Day. Or maybe “Jedburgh” was simply just the next word on a list of random code names.

One of the most popular theories, however, is that the Jeds were named after a small Scottish border town where, during the 12th Century, Scots conducted guerrilla warfare against English invaders. Legend has it that these fierce warriors wielded their Jedburgh axes with such determination that their war cry struck fear in all those who heard it. Perhaps this bit of medieval lore played a role in the selection of the OSS codename.

DCI William “Berkshire” Colby

One of the most famous Jedburghs was William Colby, who would later become Director of the CIA.

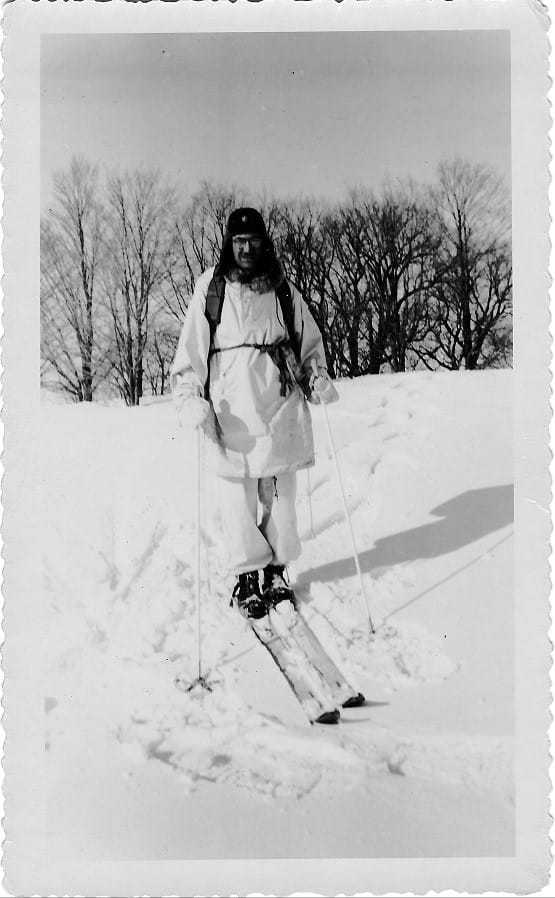

Colby (standing) leading OSS Jed Team as they prepare for mission.

Colby, whose Jedburgh codename was “Berkshire,” led a Jed team into occupied France in August 1944. He was only 24 years old. The son of an Army officer, Colby had attended Princeton and Columbia before joining the military. He cheated on an eye exam to become a paratrooper. Jump school, along with French language skills, made him a good candidate for OSS.

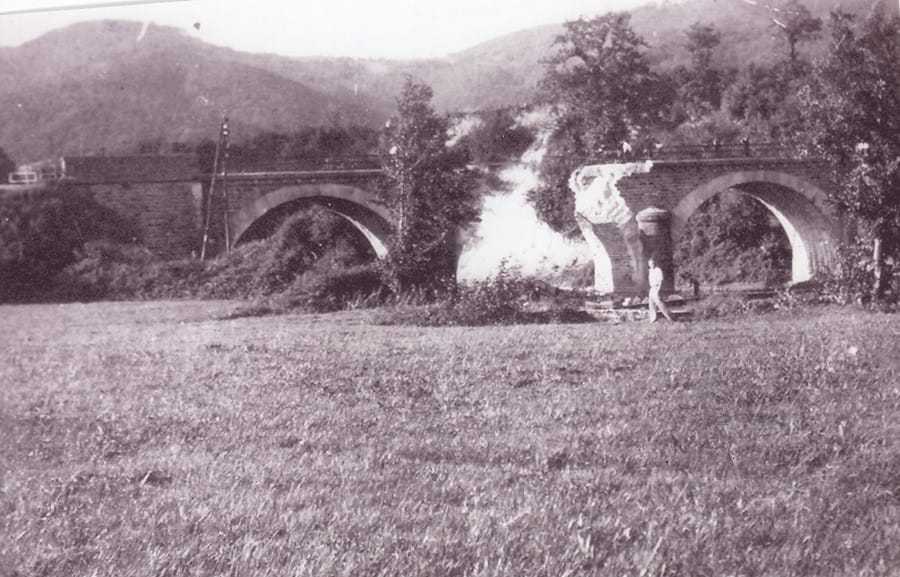

Although he more than once came within a hair’s breadth of losing his life, 50 years later Colby described the mission casually as “to harass the Germans as much as possible…ambushes on the road, blowing up bridges, that sort of thing.”

In 1945, Colby led an OSS special operations team into Norway (under the codename “Operation RYPE”) to sabotage German rail lines and prevent any German efforts to reinforce the homeland from the north. According to Colby, this team “was the first and only combined ski-parachute operation ever mounted by the US Army” during World War II.

After the war, many American Jedburghs, including Colby, joined OSS’s successor, the CIA. Colby became Director of CIA in September 1973 and served in that position until January 1976.

Several years after Colby’s retirement, he attended a gathering at Agency Headquarters where the Curator of CIA’s Historical Intelligence Collection, William Henhoeffer, delivered an address to an eager audience of French, British, and American Jedburghs. Colby warned Henhoeffer that if he heard one or two of the American Jedburghs begin to count in double-digit numbers, he’d better pay attention.

According to Colby, when American Jedburghs failed to perform training exercises well, their British instructors frequently demanded 50 pushups. The obedient but often feisty Jeds would end by chanting “46, 47, 48, 49, 50, bullshit.” Since then, on more than one occasion, they have raised the chant before any speaker whose claims seemed to seriously lack credibility.

If you ever find yourself in conversation with a WWII vet, and he starts to count in double-digit numbers, take that as a hint that you’d better tone down the rhetoric.