About the Berlin Tunnel

During the Cold War, monitoring the Soviet Union and its influence worldwide was the top priority for the CIA. In the 1950s, before reconnaissance satellites and other sophisticated collection systems were operational, wiretaps were one of the important technical means for collecting intelligence about Soviet military capabilities. The challenge was where and how to best conduct such wiretap operations.

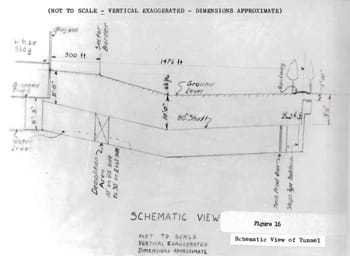

During construction of the tunnel 3,100 tons of soil were removed.

Berlin was the center of a vast communications network from France to deep within Russia and Eastern Europe. At the time, almost all Soviet military telephone and telegraph traffic between Moscow, Warsaw, and Bucharest was routed through Berlin over land lines strung overhead from poles and buried underground. In a joint effort, the CIA and British Secret Intelligence Service (MI-6) assessed that tapping into underground communication lines in the Soviet sector of Berlin offered a good source for Soviet and East German intelligence. Tunneling from West Berlin to the underground cables in nearby East Berlin was judged to be feasible and hidden from visual surveillance.

A warehouse facility was designed with a large basement to house the dirt from the tunnel.

Director of Central Intelligence Allen Dulles approved the covert tunneling and tapping operation in January 1954. Work began the following month using a US Air Force radar site and warehouse in West Berlin as cover for the construction.

The compound contained the warehouse, a combined kitchen-dining facility and barracks, and a generator building.

Construction took a year. Tunnelers removed 3,100 tons of soil (enough to fill 20 average American living rooms) and used 125 tons of steel plate and 1,000 cubic yards of grout. The finished tunnel was 1,476 feet long. British technicians installed the taps, and collection began in May 1955.

Near the entrance a shield was devised with horizontal ÒblindsÓ to mitigate the effects of a cave-in.

Unknown at the time to the CIA and MI-6, the KGB–the Soviet Union’s premier intelligence agency–had been aware of the project from its start. George Blake, a KGB mole inside MI-6, had apprised the Soviets about the secret operation during its planning stages. But to protect Blake, the KGB allowed the operation to continue until April 1956 when they “accidentally discovered” the tunnel while supposedly repairing faulty underground cables–without putting Blake at risk. The Soviets planned the discovery in hopes of winning a propaganda victory by publicizing the operation. But their plan backfired when, instead of condemning the operation, most press coverage marveled at the audacity and technical ingenuity of the operation.

125 tons of steel liner plate were used to line the tunnel.

The taps produced enormous amounts of data for almost a year:

- 50,000 reels of tape

- 443,000 fully transcribed conversations

- 40,000 hours of telephone conversations

- 6,000,000 hours of teletype traffic

- 1,750 intelligence reports.

Following the tunnel’s shutdown, processing of this immense volume of data took more than two years to complete.

The finished tunnel was 1,476 feet long Ð roughly the length of the Reflecting Pool in front of the Lincoln Memorial.

Subsequent studies determined that the Soviets had not attempted to feed false information over the tapped lines–the intelligence that had been collected was genuine. Despite the KGB’s foreknowledge, CIA ruled this most ambitious operation a success–it yielded valuable intelligence for US policymakers and war fighters, including:

- Detailed order of battle and information on activities of Soviet and Warsaw Pact forces

- Identification of people working on Soviet atomic energy projects

- Early warning of the Soviet’s establishment of an East German army

- The poor condition of East German railways

- Resentment between Soviets and East Germans

- Great tension in Poland

- Soviet inaction regarding a military invasion of Western Europe.

The Soviets planned the discovery of the tunnel in hopes of publicizing the operation. Their plan backfired when most press coverage marveled at the audacity and technical ingenuity of the operation.

Video

During the Cold War, monitoring the Soviet Union and its influence worldwide was the top priority for the CIA.

In the 1950s, before reconnaissance satellites and other sophisticated collection systems were operational, wiretaps were one of the most important technical means for collecting intelligence about Soviet military capabilities.

The challenge was where and how to best conduct such wiretap operations.

Berlin was at the center of a vast communications network from France to deep within Russia and Eastern Europe.

At the time, almost all Soviet military telephone and telegraph traffic between Moscow, Warsaw, and Bucharest was routed through Berlin over land lines strung overhead and buried underground.

In a joint effort, the CIA and the British Secret Intelligence Service, MI-6, assessed that tapping into underground communication lines in the Soviet sector of Berlin offered a good source for Soviet and East German intelligence.

Tunneling from West Berlin to the underground cables in nearby East Berlin was judged to be feasible, and Director of Central Intelligence Allen Dulles approved the covert tunneling and tapping operation in January 1954.

Work began the following month using a US Air Force radar site and warehouse in West Berlin as cover.

Construction took a year.

Tunnelers removed 3,100 tons of soil and used 125 tons of steel plate and 1,000 cubic yards of grout.

The finished tunnel was 1,476 feet long.

British technicians installed the taps, and collection began in May 1955.

Unknown to CIA and MI-6, the KGB—the Soviet Union’s premier intelligence agency—had been aware of the project from its inception.

A KGB mole inside MI-6 had alerted the Soviets during the operations planning stages.

To protect their source, the KGB allowed the operation to continue until April 1956, when they “discovered” the tunnel while supposedly repairing faulty underground cables.

The Soviets hoped to stage a propaganda coup by publicizing the operation, but their plan backfired when, instead of condemning the operation, most press coverage marveled at the operation’s audacity and technical ingenuity.

The taps collected successfully for nearly a year, and processing the immense volume of data took more than two years after the tunnel was shut down.

Subsequent studies determined that the Soviets had not attempted to feed false information over the lines—the intelligence that had been collected was genuine.

Despite the KGB’s foreknowledge, CIA ruled this most ambitious operation a success, yielding valuable intelligence for US policymakers and warfighters.