Digging Up Secrets with Indiana Jones: Archaeologists as Spies

Indiana Jones is arguably one of the greatest film heroes in the world. What many fans may not know, however, is that America’s first spy agency and CIA’s predecessor, the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) made use of Dr. Jones’ talents and experience during the Second World War.

This little-known tidbit of Indiana Jones lore was revealed in the fourth film, Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull. Following a rather fantastical scene with an atomic bomb and refrigerator, Indy mentions he worked for OSS during World War II, alongside an MI6 officer, in both the European and Pacific theatres. Recruited into the U.S. Military for the war, he apparently reached the rank of colonel while serving in OSS and won many medals for his valor.

"I had no reason to believe Mac was a spy. He was MI6 when I was OSS. We did twenty or thirty missions together in Europe and the Pacific."

Indiana Jones in Indiana Jones and The Kingdom of the Crystal Skull

Although Indiana Jones is, of course, a fictional character, many real-life archaeologists worked in the field of intelligence during WWI and WWII.

If you think about it, archaeologists have many of the skills needed by intelligence officers. They’re experts on local cultures and customs, they’re used to traveling in remote and difficult conditions, and they speak the languages of the regions in which they work. According to Dr. Juliette Desplat, Head of Modern Collections at the UK National Archives and scholar on WWI archaeologist-spies, they’re also pretty good at cracking codes. “If you can decipher cursive hieroglyphs and cuneiform inscriptions, you can crack any code.”

In honor of the fifth and final chapter of the Indiana Jones film saga, here are five real-life archaeologists who, like Indy, dabbled in the world of espionage during wartime and dug up a few secrets of their own.

"Since archaeologists are, quite frankly, historical, cultural peeping Toms, is it that surprising that archaeology and intelligence had such close links during the First World War?"

Dr. Juliette Desplat, UK National Archives

T.E. Lawrence: Lawrence of Arabia (1888-1935)

The most famous real-life archaeologist, who also was a spy, is probably Thomas Edward Lawrence, better known as Lawrence of Arabia.

Lawrence was a British archaeologist, writer, diplomat, and military officer whose exploits during WWI became the stuff of Hollywood legend; quite literally. He was played by Peter O’Toole in the epic 1962 film, Lawrence of Arabia, which was based on his memoir, Seven Pillars of Wisdom.

Lawrence got his start in 1911 working as an assistant archaeologist on a dig in Carchemish, Syria, sponsored by the British Museum. He was also sent on an expedition to map archaeological remains in the Sinai Peninsula. Lawrence fell in love with Arab culture, language, and history, and he strongly believed in Arab independence from Ottoman rule. He and his team made important archaeological discoveries and gathered significant scientific data on these expeditions. They also gathered intelligence.

In Syria, although the archaeological expedition was real, Lawrence was also there to monitor German progress on the construction of an important railway supply line linking Berlin to Baghdad, Iraq. In the Sinai, the expedition was a cover for a British military topographical survey.

When WWI broke out and Turkey aligned with Germany, Lawrence left archaeology and joined the British military. Because of Lawrence’s extensive knowledge and archaeological experience in the region, he was sent to Egypt as a second lieutenant in military intelligence. He was on a desk job for two years, but soon, he found himself in the field fighting on behalf of both the British and the Arab people. It’s his exploits during this time that garnered him the legendary reputation he has today.

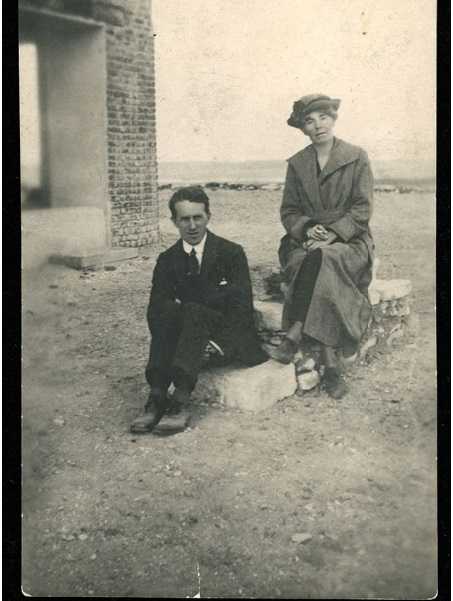

Gertrude Bell and T.E. Lawrence in Cairo, March 1921. Photo courtesy of the Gertrude Bell Archive at Newcastle University.

Gertrude Bell: Queen of the Desert (1868-1926)

Another famous WWI British archaeologist-spy is Gertrude Margaret Lowthian Bell. Bell was an archaeologist, writer, and diplomat who spent much of her life exploring and mapping Europe, East Asia, and the Middle East.

Bell is perhaps best known for her work in helping to create the modern state of Iraq. Her ideas on civil administration in Mesopotamia were the foundation for future governance of the region. She also attended the Cairo conference of 1921, where many of her recommendations were followed, including the choice of Faisal I as the new King of Iraq.

Bell was an adventurer at heart, loved mountain climbing, and frequently recorded her travels and expeditions through personal letters and photographs. In fact, her archival collection is so extensive that in 2017 UNESCO added it to their “International Memory of the World” register in recognition of its “global significance as a heritage resource.”

Gertrude Bell Archive (ncl.ac.uk)

Before WWI broke out, Bell traveled throughout Egypt, tracing the archaeological evidence of early Roman Empire frontiers in the Arabian Desert. Her private letters home found their way, unbeknownst to her, into British Intelligence’s Arab Bureau, where she soon became an invaluable resource.

During the early years of WWI, she worked alongside T.E. Lawrence in the British Intelligence Bureau based out of Cairo, and she helped him gain support for his plan to recruit Arabs to fight against the Turks. Like Lawrence, she also believed in Arab independence. In the field, she collected information on various tribal histories throughout Arabia, and in 1916 she was sent to Basra where she spied on Iraqi tribal activities.

After the war ended, and the modern state of Iraq was established, Iraqi King Faisal appointed Bell as the Director of Antiquities. In the years before she died, she helped to create the Iraqi Museum to protect Iraq’s artifacts and keep them within the country.

Baron Max von Oppenheim: "The Kaiser's Spy" (1860-1946)

The British weren’t the only ones who used archaeologists as spies during WWI.

Baron Max von Oppenheim, who was known to the British as “The Kaiser’s Spy,” was an amateur archaeologist, educated as a lawyer, and served as a diplomat. He was a German noble and a member of the Oppenheim banking dynasty. He also headed Germany’s Intelligence Bureau for the East during WWI, where he gathered intelligence and helped spread the idea of Muslim solidarity against the Allies.

Oppenheim’s greatest archaeological discovery was the ancient Neolithic site of Tell Halaf in northern Syria.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York has an exhibit showcasing the few artifacts that still exist from Tell Halaf. Within that exhibit, they have an audio story that explores Oppenheim’s discovery of the site and illuminates the murky boundaries when archaeology and spying collide.

A Spy Story (Audio) | The Metropolitan Museum of Art (metmuseum.org)

According to the Met, Oppenheim was a 39-year-old German diplomat living in Cairo when he arrived in the village of Tell Halaf in the summer of 1899. He was on his way to Baghdad to establish a route for the railroad that would connect Iraq to Berlin, the same railroad Lawrence was sent to surveil. Local tribesmen in Tell Halaf led Oppenheim to the site where he’d one day discover the remains of an entire ancient city.

In 1929, the French and British authorities, who controlled the area, were suspicious of Oppenheim’s archaeological motives and thought he might be a spy. He had been visiting the same area between Syria and Turkey for the past thirty years, and they were concerned he might be creating secret maps of the region for the German military, radicalizing the Bedouin tribes, and preparing a coup against the colonial powers.

In this case, Oppenheimer may have genuinely been acting on behalf of historical and archaeological interest, not intelligence. After all, according to Dr. Desplat, “Max von Oppenheim was a brilliant scholar, but a rather poor spy.”

Baron Max von Oppenheim in 1917.

Rodney Young: Codename Pigeon (1907-1974)

Dr. Rodney Stuart Young—a renowned American archaeologist whose discoveries include the palace where King Midas, of the legendary golden touch, once resided—ran the OSS Secret Intelligence Unit for Greece during WWII.

Young, a Princeton graduate, left the U.S. in 1929 to attend the American School of Classical Studies in Greece, the oldest and largest overseas U.S. research center, to participate in its archaeological excavations. He grew to love Greece and the Greek people. When WWII broke out, Young volunteered as an ambulance driver with the Greek Red Cross. He was injured in an Italian air raid and returned to Washington, D.C., where he was soon recruited into the newly formed OSS.

The OSS was impressed by Young’s knowledge of the region, so they asked him to run the OSS Secret Intelligence Branch on Greece. Young recruited several more archaeologists into OSS.

According to Susan Heuck Allen, the author of Classical Spies: American Archaeologists with the OSS in World War II Greece, the new recruits didn’t use archaeology as a cover because, “its overuse by the British Army—they famously commissioned T. E. Lawrence (of Arabia) in WWI—rendered it a ticket to the firing squad. So they scrambled for postings as visiting professors, relief workers, and military or commercial attachés in that hotbed of spies, neutral Turkey.”

In 1943, Young set up the OSS Greek Desk in Cairo. Young and his team of archaeologists conducted 27 field missions, some quite dangerous.

According to Allen, “They gathered military intelligence to guide U.S. Army Air Force bombing raids on Hitler’s oilfields in Romania. They reported political intelligence on left wing guerrillas… [and] they collected economic intelligence to guide postwar reconstruction… But mostly they itched to get back to excavating in Greece.”

After the war, Young served as a special assistant for post-war humanitarian relief in Greece. He went on to become a full-time professor, like Indiana Jones, while still going out on archaeological expeditions. He even served as president of the Archaeological Institute of America from 1968 to 1972.

FUN FACT: "The OSS Greek Desk in Cairo used bird names, such as Pigeon, Sparrow, Chickadee, Owl, Thrush, Vulture, Eagle, and Duck. Their subagents were given code names related to theirs. One archaeologist who worked under ‘Duck’ sported the moniker ‘Daffy’."

Susan Heuck Allen, author of Classical Spies

Jack Caskey: Operation Honeymoon (1908-1981)

Dr. John “Jack” Langdon Caskey was an American archaeologist, professor, and distinguished scholar. During WWII, however, he helped save the life of a young, beautiful female double agent who was being hunted by the Nazis. The information she provided to the Allies was instrumental in the downfall of Cicero, one of the most notorious German spies of WWII.

Throughout his lifetime, most of Caskey’s friends and colleagues knew him as the head of the Classics department at the University of Cincinnati, or as the director of the American School of Classical Studies in Greece. He spent most of his career making significant archaeological finds, including one of his most famous at Lerna, the legendary site of mythological hero Hercules’s battle with the nine-headed monster called the Hydra. In 1980, he was awarded the Gold Medal for Distinguished Archaeological Achievement by the Archaeological Institute of America, a significant accomplishment in his career field.

In his early years, however, like many of the archaeologists affiliated with the American School of Classical Studies in Greece in the 1940s, Caskey went to work for the OSS. He ran the OSS base in Izmir, Turkey, one of the most critical within the Greek Desk’s mission.

It was while he was stationed in Izmir that he played a key role in the success of “Operation Honeymoon.”

Cicero, whose real name is Elyesa Bazna, was an Albanian Turk who had infiltrated the British Embassy in Ankara on behalf of the Germans by getting a job as the Ambassador’s valet. Much of his intelligence ended up on Hitler’s desk.

According to author Susan Heuck Allen, Cicero provided the Nazis with information on, “the Moscow, Cairo, and Tehran conferences, disagreements between Churchill and Roosevelt over the European invasion route, and British attempts to pressure Turkey into joining the Allies.” He even provided the Germans with intelligence on the planned D-Day invasion.

It was a young, blonde German secretary named Nele Kapp who discovered Cicero’s identity. Kapp worked for the German military attaché in Ankara, Ludwig Moysich, who was actually a spy. She wanted to defect from Germany, so she began stealing secrets from Moysich, and provided them to the Allies.

When the Nazis found out about her betrayal, they ordered her captured “dead or alive.” She needed to flee the country, but British Intelligence believed the mission was too risky, so they asked Caskey if he and OSS could help. Under the light of the pale moon, Caskey orchestrated her daring nighttime escape in a small fishing boat. The operation was known as “Honeymoon” because Kapp and her British escort posed as newlyweds during the escape.

If this sounds like the premise of a Hollywood movie, it is! The Cicero spy story became the subject of a 1952 film called, Five Fingers. Caskey’s role in the spy caper, of course, was kept hush, hush.