In Nathan Hale’s time during the early years of the Revolutionary War, spying was not exactly considered honorable. But Hale believed in America and was willing do anything in his power to defend American freedom. He volunteered to spy on the British Army after reportedly confiding in his classmate that he longed to be useful and that every kind of service for the public good was honorable by being necessary.

Early life of an American Patriot

Nathan Hale was born to a prominent Connecticut family in 1755 and attended Yale University (then known as Yale College) with hopes of becoming a teacher. He graduated with honors in 1773 and began teaching in New London, Connecticut.

When the Revolutionary War began in 1775, Hale recognized the importance serving in the military to fight for America’s independence from Britain. He joined the Connecticut militia, becoming a First Lieutenant within five months. For reasons unknown, Hale was unable to join his troops on the battlefront during the Siege of Boston, which deeply troubled him.

Answering the Call to Serve

Hale, intensely eager to go to combat against the Redcoats, leapt at the opportunity to serve in the newly established Knowlton’s Rangers. General George Washington, then commander of the Continental Army, established the elite group under the command of Lt. Col. Thomas Knowlton and tasked it with carrying out reconnaissance and raids.

After the Continental Army’s defeat at Brooklyn Heights in August 1776, Washington was forced to move his army into Manhattan as the British took control of Long Island. Washington desperately needed intelligence on their next move.

Knowlton gathered his men, updated them on the dire situation, and asked for volunteers willing to go undercover and cross enemy lines. The Rangers voiced their willingness to die in battle but disdain for dying in disguise. Ultimately, only one answered the call. Nathan Hale.

Hale viewed the call to spy against the British as his chance to serve in a meaningful way.

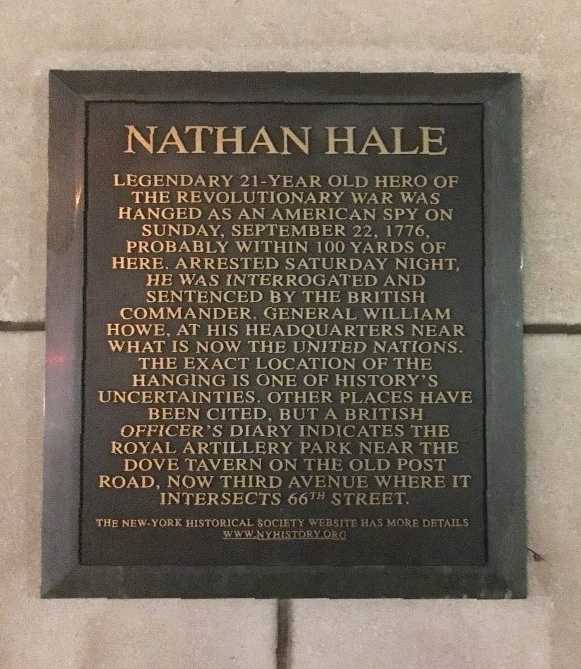

A plaque in Manhattan noting the spot where Nathan Hale was hanged.

The Fateful Mission

On the night of September 15, 1776, Hale left for Long Island outfitted as a schoolmaster and carrying his Yale diploma. He was using the cover story that he was a teacher looking for work.

Details of Hale’s espionage activities and capture are scant, though he almost certainly traveled around Long Island taking copious notes of British movements and fortifications just before his discovery.

On the morning of his execution on September 22, 1776, Hale showed great dignity and composure. His final words are purported to be: “I only regret that I have but one life to give to my country.”

The Legacy

A statue of Nathan Hale—one of several replicas—was unveiled at CIA Headquarters on 6 June 1973, the bicentennial anniversary of Hale’s graduation from Yale. A CIA statement released on that occasion praised Hale as “the country’s first intelligence officer.”

Though there is no known portrait of Hale, the sculptor—artist Bela Lyon Pratt who was commissioned by Hale’s alma mater, Yale University—used a local man who was the same age as Hale to serve as inspiration. Pratt’s original statue of Hale went on display on Yale University campus in 1914.

The statue captures the spirit of the moment before Hale’s execution. A 21-year-old man prepared to meet his death for honor and country. His hands and feet bound, face resolute, and gaze fixed on the horizon.

The Agency, steeped in tradition, holds to the legend that placing a quarter—which bears the face of Washington whom Hale served under—around Hale’s statue will ensure the safety of officers preparing to leave for an assignment.