How good are your survival skills? Could you live in the mountains in the middle of winter with limited food and supplies? Would you be willing to use your skills and risk your life in service of your country?

America’s history is rich with stories about courageous men and women who have gone above and beyond to protect their nation.

The story of Office of Strategic Services officer Roderick Stephen Hall and the Brenner Pass assignment is one of the most amazing and inspiring stories.

Steve survived for six months in the Italian and Austrian Alps while planning sabotage missions targeting Nazi supply routes.

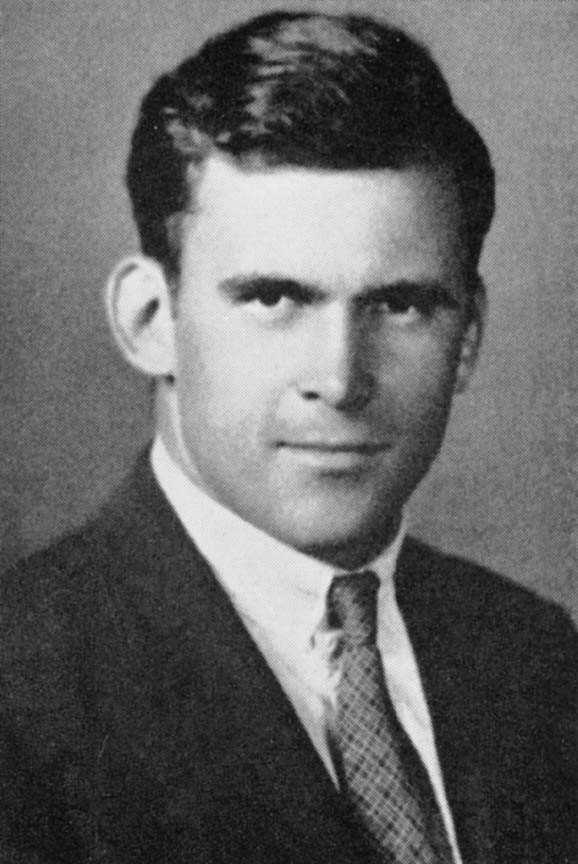

Stephen Hall

A Seasoned Traveler

Roderick Stephen “Steve” Hall was born in Peking, China, in 1915. His father was a successful international businessman and his mother was a doctor. As a young man, Steve attended Phillips Academy Andover.

After graduating in 1934, Steve traveled the world seeking adventure. During his travels, he became an avid outdoorsman. Steve also became very familiar with the Italian Alps — in particular, the Brenner Pass — while he hiked, skied and climbed his way through the area.

Searching for Adventure

After the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the United States entered the Second World War.

Steve had just returned home from his latest adventure and enrolled at Yale University. However, academic life did not fulfill his yearning for purpose and he dropped out to enlist as a private in the US Army.

Steve’s eagerness to learn and take on new projects served him well. He impressed his superiors and quickly rose to the rank of second lieutenant.

After 10 years of adventure, Steve decided to use his survival skills and knowledge of the Brenner Pass to help his country.

After 10 years of adventure, Steve decided to use his survival skills and knowledge of the Brenner Pass to help his country.

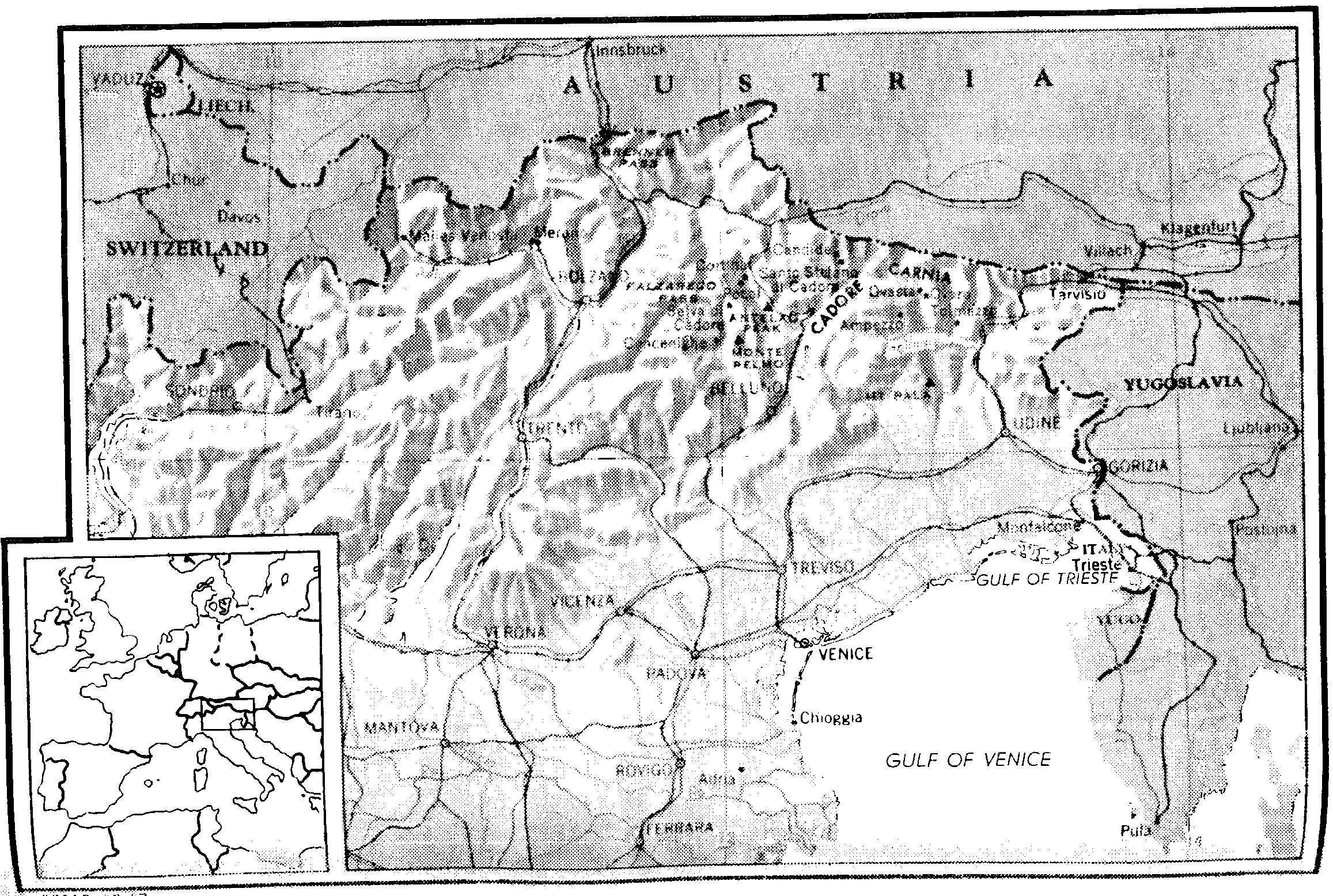

During the war, the Brenner Pass was of vital importance to the Axis powers as a supply route to the Mediterranean.

Map of Alps where Steve operated.

A Bold Plan

In the fall of 1943, Steve wrote a letter to officers at the fledgling Office of Strategic Services (OSS) — the predecessor of the CIA — proposing one of the most amazing sabotage missions of World War II.

It seems to me, who knows nothing about your organization [OSS], that finding an agent with the necessary personal accouterments to go to Cortina [on the southeast approaches to the Brenner Pass] and carry out missions of sabotage, political organization, reconnaissance, or whatever is desired would be difficult. Even if he was a European, he would encounter official questioning at every turn now, with danger of exposure each time. And traveling by land, how could he carry sufficient explosive and tools to effect sabotage himself, if all other plans failed?

These obstacles could, of course, be overcome one way or another; but here is my suggestion, based on the premise that the sabotage is more important in the near future than political organization:

Drop a man by parachute on the open country between Pocol and the Falzarego Pass and drop enough Army “Mountain Rations” and personal equipment to sustain him indefinitely in the peaks, if necessary. Drop TNT and a tool kit. I believe one could get away with it, if the jump was made in the early dawn when mist rises profusely over the terrain, or through a snow fall.

This man, if he was a good rock and snow climber, and skier, would have no trouble in moving about the valley unnoticed even in the daytime. The matter of tracks in the snow is of no consequence; paths and brooks could cover his movements, and he could always take to the mountain rock.

Operating even under adverse conditions, this man, I believe, could block the Ampezzo highway and railroad beyond use during the winter, anyway, within 3 days after he landed. It should be possible for him to blow out the Drava River roads within another 10 days. Thereafter he could work on whatever opportunities presented themselves.

I feel sure he would not have to search out anti-Nazi elements for laying the plans for continued sabotage: they would come to him. Of course, the problem of how he would get out and save his own skin is all a matter of chance and circumstance. Perhaps he would have to perch on the peak of Antelao nibbling concentrated chocolate until German capitulation.

I would be willing to do the job—and I think I could. Here are my qualifications:

- Trained in military demolitions.

- Trained in mapping, reconnaissance, communications, and similar subjects (am battalion S-2).

- Familiar with the Val Ampezzo, particularly the little-known paths and minor terrain features, from walks and skiing. Skilled in rock and snow climbing, with 15 years experience on the cliffs and snow of N.E., in Wyoming (Grand Tetons ), and Cortina. … Expert rifle and pistol shot since 1930—Nat’l Rifle Association and Army.

- Physically: somewhat above average endurance; accustomed to living in the open under all conditions; no major operations, illnesses or frailties; 28 years of age.

- Education: … Am no linguist, but … picked up enough Italian in 5 days at Cortina to get about conveniently …

- Personal situation: unmarried, … ready to go anytime under any circumstances that augur success.

Cordially yours,

R.S.G. Hall

2nd Lt. 270 Engr. (c) Bn.

Camp Adair, Oregon

Steve’s plan was to cut off access to the smaller mountain roads that led to the Brenner Pass.

Steve did not think his letter would get any attention, but he was in for the surprise of a lifetime. His idea caught the attention of the Special Operations (SO) branch of the OSS, which was responsible for sabotage, guerrilla warfare, and other subversive activities. Steve received a letter from the OSS which ordered him to report to Washington, DC.

Training for the Adventure of a Lifetime

After a brief orientation at the OSS headquarters, Steve was sent to a nearby base for training. There, he learned hand-to-hand combat, sabotage techniques, demolitions, and guerrilla warfare tactics.

After graduation, Steve was sent to North Africa to work as a demolitions instructor. His time there did not last long. On June 22, 1944, Steve was pulled out of the demolitions school in Algiers and sent to Caserta, Italy. There, he met with Company D from the 2677th OSS Regiment, who would help him carry out his mission. Steve laid out his plan to cripple the Brenner Pass and had no trouble gaining the support of his men.

Preparations for the mission began. Steve was sent back to Algiers for a crash course in parachuting. Next, Steve gathered the mountaineering equipment his team would need for the mission and took them on an eight-day training run in the Italian mountains where they honed their language and outdoor survival skills.

Driving the Germans to Distraction

On the night of August 2, 1944, Steve and his team were finally ready to begin the mission. They were dropped at Monte Pala in the foothills of the Alps of northern Italy. Unfortunately, Steve and his team would have to travel 85 dangerous miles to the Brenner Pass, so their real mission did not begin until a week later.

In the dark of the night, Steve and his team crept toward a bridge north of Tolmezzo, Italy. The bridge was so deep in enemy territory that it was unguarded. Steve placed a charge on the bridge and so heavily damaged the structure that it could not support heavy loads.

Steve and his team continued the mission along the way to the Brenner Pass by targeting smaller bridges that were important to communications and motor vehicle supply routes. However, Steve never made it to the Brenner Pass.

The End of the Journey

The snow spit and spun and froze the landscape for days on end, a blizzard engulfing Steve and his team. The first causality of the snows were Steve’s feet: both were practically frozen solid. He had crossed a high mountain pass on a mission, almost starved to death, and found his way to sanctuary in a tiny village near the forest of Todesch di Vallada, where he attempted to heal his feet by soaking them in a vat of grease. He hoped to lie low until the end of the war.

A few weeks later, on January 25, 1945, Steve set off to the north on skis in a blinding snowstorm under orders to blow up the hydroelectric plant at Cortina. He never made it. The sun was barely over the horizon the next morning when a game warden found Steve, his feet so frozen and swollen that he couldn’t escape. Steve hid out with a local priest while the warden promised to get help. The warden instead turned him over to the Fascist police. They had identified Steve after one of his own partisan fighters betrayed him to the Nazis.

Steve was turned over to German S.S. guards at the Bolzana concentration camp, tortured for two weeks, and then hung from the steam pipe in the torture room on February 20, 1945. Because he was in uniform, his murder was a direct violation of the Geneva Convention on prisoners of war. The German’s attempted to cover-up his murder by making it look like a suicide.

After the war, an Italian doctor who was also a prisoner at the concentration camp admitted to having signed a death certificate for “Roderick Hall,” claiming the cause of death was heart failure. He was never allowed to examine the body.

“Knowing that my refusal to prepare the requested death certificate would lead to the corpse’s clandestine burial in an unidentified grave,” confessed Dr. Karl Pittschieler, “I prepared the certificate, showing “paralisi cardiaca” (cardiac paralysis) as cause of death.”

After the war, OSS officers entered the camp, searched the records, and found the death certificate. They were able to locate Steve’s grave with that information and give him a proper military burial. The records were also used as evidence to help convict Steve’s killers of murder.

In January 1946, the four officers accused of Steve’s murder were tried before an American Military Commission in Naples, Italy. One was sentenced to life imprisonment and three were hanged.

The OSS posthumously awarded Steve the Legion of Merit — one of the most distinguished military decorations.

Testimony during the trial of Steve Hall’s murder.

The Letters

Steve was a prolific letter writer, never short for words. During his mission, he wrote several intriguing letters to his superiors describing what was happening in the field and his future plans. Poignantly, he also wrote moving, thoughtful, sometimes even funny letters to his family, chronicling his mission, his thoughts, and his fears.

These letters were given to trusted locales–peasants, nuns, and partisans–to be smuggled out of the war zone, or hidden in buried bottles to be found after the war. We are lucky to have these letters as part of America’s historical legacy.

The letters also helped in the prosecution of Steve’s killers. They are an invaluable and priceless testament to Steve’s heroism and dedication to the country he loved.

To hear from Steve in his own words, read some of his original letters published in CIA’s Studies in Intelligence. You’ll also find written testimonies by witnesses and fellow officers that were used to convict Steve’s Nazi killers during the American Military Commission trials Italy.