The world’s most famous magician, Harry Houdini, was known as a celebrity conjurer, a practitioner of escape magic, and a master illusionist. He’s had an enduring legacy on the magical arts since his untimely demise on Halloween Day, 1926. That’s why October 31st is known in magical circles as “National Magic Day” or simply “Houdini Day.”

In honor of this legendary magician, we’re exploring the effect magic, and even Houdini, has had in the realms of intelligence and espionage.

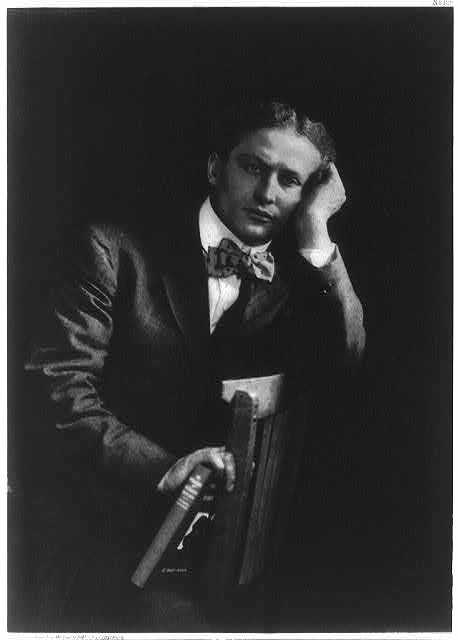

Harry Houdini, courtesy of the Library of Congress

It may surprise people to learn that Houdini’s magical techniques have influenced generations of clandestine officers. We even had a former CIA deputy director who was a magician himself!

But was Houdini more than just an influential figure?

Was he ever a practitioner in the art of espionage?

Was he a spy?

To answer these questions, we must first delve into the mystery of the missing magic manuals of Langley and the CIA’s first magician, John Mulholland.

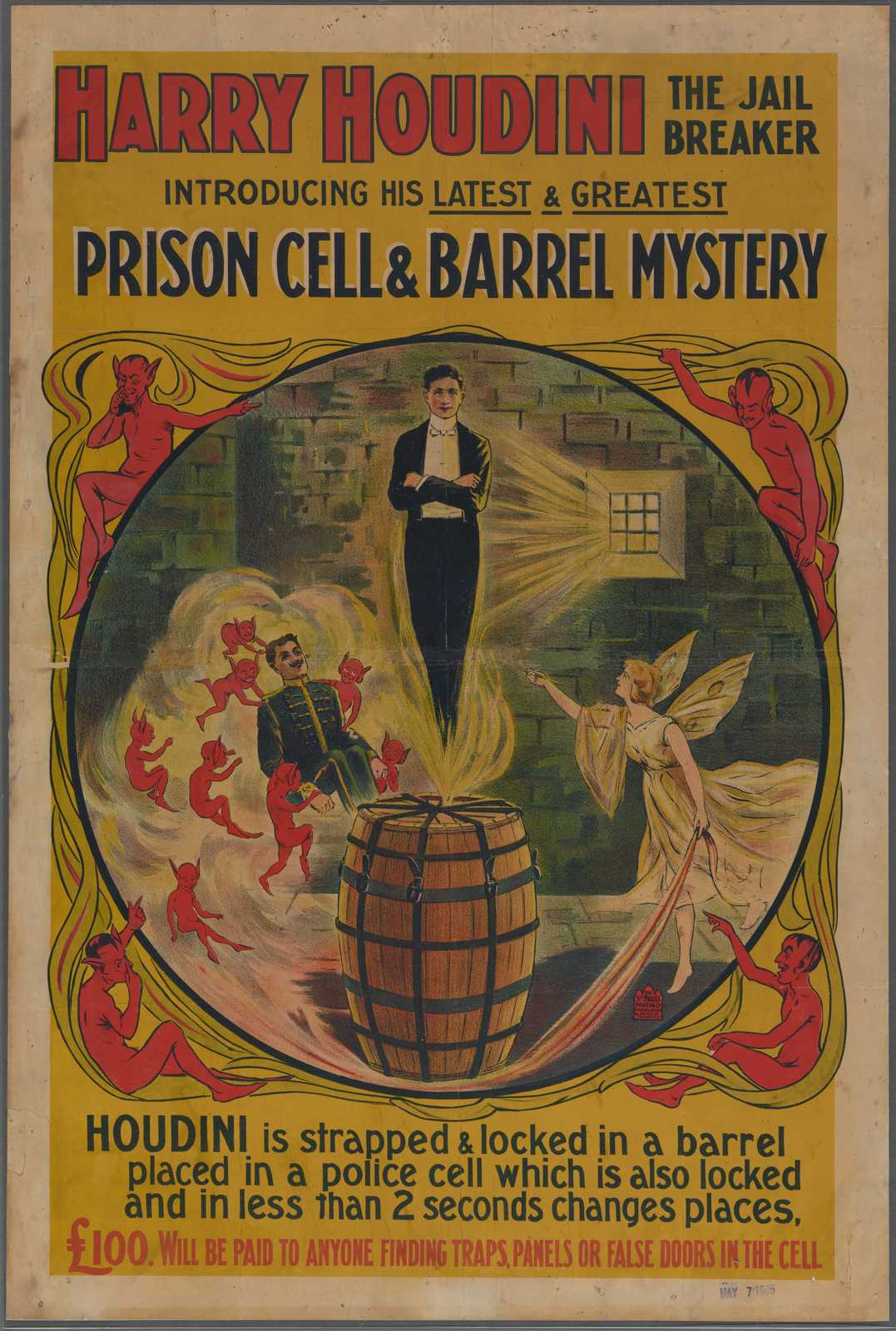

Vintage poster for Harry Houdini show, courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Magic and Espionage at CIA

“Magic and espionage are really kindred arts,” or so wrote former CIA Deputy Director McLaughlin, an amateur magician himself, in the forward to the book, “The Official C.I.A. Manual of Trickery and Deception” by H. Keith Melton and Robert Wallace.

This book, created from two long-lost training guides designed to teach Agency officers how to integrate elements of the magician’s craft into clandestine operations, revealed that the CIA’s connection to the world of magic was decades old.

In the 1950s, as part of the MKULTRA project, the Agency hired magician John Mulholland to teach young officers techniques of deception suitable for the field, such as smuggling assets out of East Germany during the Cold War in vehicles that resembled the magic boxes used in stage illusions.

As part of his contract, Mulholland prepared two training manuals; “Some Operational Applications of the Art of Deception” and “Recognition Signals.”

In 1973, when then-CIA Director Richard Helms ordered the destruction of all documents associated with the MKULTRA program, the manuals were thought to be gone forever.

Then, in 2007 while going through some unrelated documents, Robert Wallace, a former director of the CIA’s Office of Technical Services, discovered references to the manuals and tracked down poor-quality copies of each that had somehow escaped the shredder.

Believing that the manuals merited publication in full, Wallace conferred with his co-author, intelligence historian and collector Keith Melton, to produce “The Official C.I.A. Manual of Trickery and Deception,” which included illustrations of stage deception techniques, such as Harry Houdini’s walk through a wall.

In fact, many of Houdini’s magical escape techniques are discussed in the now declassified manuals, as they have influenced later generations of clandestine officers as well as spy gadgetry developed during the Cold War.

According to the Trickery and Deception book, concealment devises like magic coins and the hollow Mokana shoe used by Houdini for hiding escape tools became popular among spies throughout the Cold War era.

Even the Office of Strategic Services, the CIA’s WWII predecessor, was inspired by Houdini when they created tiny tools that mirrored those first used by the magician in his concealed escape kits.

It’s no wonder then that many historians of magic and intelligence have found themselves pondering the question: Was Harry Houdini… a spy?

Hungarian born magician and escapologist Harry Houdini (1874 – 1926) being fitted into an escape proof suit. (Photo by MPI/Getty Images)

The Master of Deception, Harry Houdini

Since Houdini’s death, there has been an on-going debate among historians as to whether or not Houdini was ever a “spy.”

The greatest and most recent kerfuffle was the publication in 2006 of “The Secret Life of Houdini: The Making of America’s First Superhero” by William Kalush and Larry Sloman, who conducted exhaustive research into the history of magic, eventually creating a fully text-searchable database of 700,000 pages of material, which contains thousands of references to Houdini.

Kalush and Sloman posit that the only reason Houdini would abruptly leave the United States in 1900, when he had finally achieved notoriety—and a paycheck equivalent to $45,000 a week—was because he was engaged in espionage. Houdini was rumored to be providing the German police with information about wanted criminals, as well as unspecified information to Scotland Yard Superintendent William Melville, monitoring anarchists in Russia, and helping the U.S. Secret Service with their anti-counterfeiting mission.

As author and Houdini memorabilia collector Arthur Moses noted, “Some of it may be true, but it’s hard to believe it’s all true.”

Kalush reportedly viewed documents suggesting that Houdini provided information to Scotland Yard early on; however, former International Spy Museum historian Thomas Boghardt pointed out that the commonly accepted “birthdate” for British intelligence is 1909, several years after Houdini was on-the-scene.

Boghardt also noted that Melville was focused on counterespionage in England rather than on foreign intelligence.

Harry Houdini standing next to President Teddy Roosevelt, 1914, courtesy of the Library of Congress.

A Spy for America?

Intriguingly, some historians theorize that Houdini was indeed an intelligence officer of sorts, but not for Britain, rather for his beloved adoptive homeland, the United States, then led by his friend President Theodore Roosevelt.

Houdini and Roosevelt reportedly met in 1893, when Roosevelt was still hunting buffalo and Houdini was working the Midway at the Chicago World’s Fair. They met again during the 1896 U.S. Presidential campaign, when Houdini was returning from Nova Scotia and Roosevelt was the New York City police commissioner.

As proponents of the “Houdini spied for America” argument surmise, Houdini was able to help a furious Roosevelt get back at Moscow after a Russian spy reportedly stole an eleven-hundred-page tome entitled, “The Cipher of the Department of State.”

That spy, Ivan F. Manasevich-Manuilov, had finagled his way into a job at the US Embassy in Moscow as a copyist, where he was likely able to access and steal the book.

Houdini happened to be in Moscow at the time to serve as “Court Conjuror” to the Czar for the summer and fall of 1903.

According to several historians, including Roosevelt biographer Edmund Morris, this opportunity was undoubtedly relayed to the President, who likely asked Houdini to report on what he saw and heard while in Russia.

But does this make Houdini a spy?

Historian of magic Richard Kohn believes that it would be a stretch to call Houdini a spy in “the James Bond sense.” Instead, he considers Houdini more of an “observer who passed along observations.”

Similarly, magician and paranormal debunker James Randi commented, “If Houdini had been a spy that would have gotten out. He never would have been able to sit on it.”

No doubt historians will continue to debate this question, but nonetheless master of deception Harry Houdini seems to merit at least an “honorable mention” in the pantheon of intelligence practitioners.

Harry Houdini, courtesy of the Library of Congress.