George Washington conducting a land survey. [Painting by Henry Hintermeister]

What would it be like to be randomly called upon to undertake a critical mission for your nation? And what if that mission would ultimately change the course of world history? Well, that’s exactly what happened to George Washington, who was born in the British colony of Virginia in 1732, had no formal education, and became a land surveyor when he came of age. Most Americans know George Washington as our first President. Many, however, may not know that his presidency, and our nation’s very existence, were made possible through his mastery of intelligence.

"There is nothing more necessary than good intelligence to frustrate a designing enemy, and nothing requires greater pains to obtain."

George Washington

Let’s take a look at key moments in Washington’s life to find out what intelligence lessons he learned.

1) Know your adversary

In 1753, the governor of colonial Virginia tapped the young surveyor to serve as a special envoy. Washington was to warn the French to stop building fortifications on already-claimed British territory. He was 21 years old and eager to carry out the responsibility.

Washington assembled several frontiersmen and a French speaker to join him on the journey of nearly a thousand miles. He took copious notes on the land, French military posts, as well as interactions with American Indians and others they encountered along the way.

French military personnel intercepted Washington’s party in an area of Ohio Country in present-day western Pennsylvania. They graciously welcomed and escorted the Americans to their base where Washington could deliver the message. Contrary to the French officials’ diplomatic response, the interpreter understood their actual plan was to maintain control of the contested area.

Washington delivering the Virginia governor’s letter to the French. [Getty Images]

Soon Washington departed to report the findings back to the governor. He did not get far before he crossed paths with an Indian guide who shot at him at point-blank range. Fortunately, the shooter failed, or the fate of our country would have played out much differently. Washington disarmed and released the gunman but surmised he had been sent by the French to waylay him.

Washington had little prior knowledge of the French or the remote land they occupied, but his mission taught him the importance of analyzing the adversary’s tactical terrain and strategic intent.

2) Hone your soft skills

The French liked to entertain and thought the arrival of the colonial visitors would be a good opportunity to gain information on their British rulers. Washington, however, remained discreet and proved better at diplomacy and elicitation while socializing with them. An excerpt from his journal indicated that the wine “soon banish’d the restraint which at first appear’d in their conversation & gave license to their tongues.” As the Latin saying goes: In vino veritas.

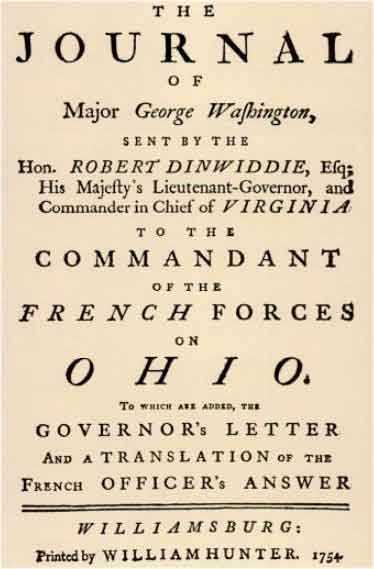

On his long journey there and back, Washington encountered various people, including the would-be assassin and French deserters. He had a knack for putting others at ease to speak frankly and debriefed anyone who might have useful information, or human intelligence. Then he logged his findings. Washington did not realize at the time that his journal contained valuable intelligence for the British and would be published in the colonies and distributed to readers across the pond.

George Washington’s published journal

Soft skills are indispensable to intelligence activities. Washington’s diplomatic mission tested his ability to take initiative, adapt to changing tasks and circumstances, and communicate effectively.

3) Collect current intelligence

Washington’s intelligence findings hardened British resolve to confront the French encroachers. In 1754, a few months after the success of his first mission, he was promoted within Virginia’s colonial militia and charged with leading a couple hundred troops to build and secure a military supply route while forcing out the French.

As Washington trekked through the frontier, he observed canoes leading up to Fort Duquesne to get an idea of how many Indians were loyal to the French. Washington’s own Indian allies also alerted him to the enemy’s presence. Clearly outnumbered, they needed the offensive advantage. They scouted an elevated vantage point and ambushed a French encampment below. Historians would later call this small clash “the shot that set the world on fire” because it marked the start of the French and Indian War in colonial America, which would expand into the global Seven Years War.

The Americans moved on to build Fort Necessity. However, Washington and his men failed to keep tabs on the location of the enemy who were now in hot pursuit. This time, the French and their Indian allies secured the high ground. Musket fire rained down; only after running out of ammunition did they allow Washington to surrender and retreat with his surviving troops.

The success of Washington’s first military skirmish and his subsequent battle defeat underscored the need to collect timely intelligence on the adversary.

Washington signing a letter of surrender before capitulating to the French and their Indian allies at Fort Necessity. [Getty Images]

4) Know your blind spots

Washington returned to Virginia and left the militia after his command took significant losses. However, his respite was brief. In 1755, General Edward Braddock had another mission for him. Britain had sent Braddock and two British Army infantry regiments to America to engage the French in open combat. They wanted Washington to serve as Braddock’s adjutant.

Braddock was 60 years old and a seasoned warfighter. His style of fighting and life experiences were very different from that of his 23-year-old adjutant. Most obvious, the British soldiers in their red coats were conspicuous even from afar. Washington became increasingly nervous about their vulnerability as the British column marched toward the French. He offered to use some of his men to scour the woods in the front and on their flank to provide intelligence. Braddock refused. He believed that the ragtag American militia may not be able to contend with Indian “savages” but that the professional British Army could. His analytic blind spots would be his downfall.

Meanwhile, at Fort Duquesne, the French and their Indian allies decided to attack the British once they began crossing the Monongahela River. The smaller French contingent, seizing on the element of surprise, overwhelmed the British. Within minutes, nearly two-thirds of Braddock’s men were either wounded or killed in the intense fighting, including Braddock himself. Washington had multiple near-misses before leading a measured retreat back to Virginia.

Washington understood the value of reconnaissance, yet Braddock’s closed mindset caused him to dismiss his advice and underestimate the enemy.

Washington survives the Battle of the Monongahela, but General Braddock is mortally wounded, and his British Army is routed. [A print of the “Washington the Soldier” painting from the Library of Congress]

5) Cultivate a circle of trust

Washington soon became the full Colonel in charge of Virginia’s militia. For a third time, he led his men alongside the British to confront the French at Fort Duquesne. When the French got word of the British and colonial advance, they abandoned their fort after burning it to the ground. Fort Pitt was built in its place, and Washington returned to Virginia.

Over the next few years, Washington became disillusioned with the British Army. Despite his heroic service and sacrifice with the militia, the British looked down on his colonial command and refused to allow him to join their ranks. He resigned from the militia in 1758 to focus on civilian life.

Many more years passed and the American colonies were in flux. Grievances built up against British rule, increasing calls from the colonies to become independent. Washington agreed. On the other hand, many colonists remained diehard loyalists. If relations between the colonies and the British deteriorated to the point of conflict, the colonies needed more than their militia. The Continental Congress in 1775 unanimously appointed Washington to build and command a new Continental Army.

From an intelligence standpoint, Washington understood that not all colonists opposed the British. He was mindful of who he trusted to further the American cause for independence.

"The necessity of procuring good intelligence is apparent and need not be further urged—all that remains for me to add, is, that you keep the whole matter as secret as possible. For upon secrecy, success depends…"

George Washington

General George Washington, Commander of the Continental Army. [National Park Service website]