Months before Japan launched its surprise attack at Pearl Harbor, the United States set the gears in motion to confront the looming threat. Once the U.S. declared war, CIA’s forerunners would play a key role. But before we get to the nation’s foray into centralized intelligence, let’s set the scene for one of Hawaii’s own, called to serve.

Peace Before the Storm

The late 1800s saw a wave of Chinese immigrants settling in Hawaii and working in agriculture. Life wasn’t easy, yet it did not take long for the hardworking immigrants to climb the economic ladder and succeed in small business. When granted the opportunity, they became proud American citizens.

Archie Chun-Ming was among the next generation, born in Hawaii in 1904 and the youngest of nine children. Fluent in English and Cantonese, he attended Honolulu’s prestigious Punahou School and went on to earn degrees from Columbia University in 1928 and Rush Medical College in 1932. Staying true to his Hawaiian roots, after graduation Archie came back to practice medicine in his hometown.

Dr. Archie Chun-Ming

Fast forward nearly a decade, and the doctor would play a vital role for the country.

In June 1941, Archie, who was also an active community organizer, served as President of the Hawaii Chinese Civic Association, which was established in 1925 to support Chinese Americans’ civil rights and to encourage Chinese Americans’ engagement in civil service and local elections. The organization worked alongside other local Chinese American clubs to support Allied war efforts before the U.S. entered the war.

Sunday, December 7, 1941 was just another day in paradise until a large group of Japanese airplanes appeared in the blue skies over Hawaii around 8:00 am. Then, the bombs and torpedoes fell. Explosions sent shockwaves through the air as military personnel getting battle-ready swore and shouted instructions. Japan’s effort to immobilize the Pacific Fleet was underway.

When the smoke settled, the Japanese had sunk or destroyed more than a dozen U.S. Navy ships and damaged hundreds of aircraft. 2,403 Americans lost their lives and more than 1,100 were wounded.

Japanese planes attack Pearl Harbor, December 7, 1941. [Photo from nps.gov, National Park Service]

The United States, formerly neutral amid the war raging in Europe, declared war the next day.

Genesis of Det 101 and its Intrepid Recruits

In January 1942, U.S. Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall appointed Major General Joseph Stilwell as Commander of American forces in the China-Burma-India theater. Shortly thereafter, a deputy of General William Donovan—who founded America’s first centralized intelligence agency following the intelligence failure of Pearl Harbor—asked Stilwell about deploying a specially-trained detachment to carry out intelligence and sabotage operations behind enemy lines.

Donovan’s soon-to-be Office of Strategic Services (OSS), CIA’s wartime predecessor, established Detachment 101, or Det 101 for short, in April 1942. Carl Eifler, an Army infantry commander serving in Hawaii and a good friend of Stilwell, led this new detachment. It was the first U.S. military unit dedicated to clandestine warfare even though the number “101” suggested a storied history.

Eifler handpicked several members of his regiment for Det 101, including Army Medical Corps Captain Archie Chun-Ming.

Having grown up on Oahu, Japan’s blitz attack at Pearl Harbor must have weighed especially heavy on Archie. He was 37 years old when Det 101 came calling and, at first, Eifler wasn’t sure he would even sign on. However, Archie’s sense of humor endured and his true professional and patriotic spirit overcame any doubt. When asked if he wanted to be part of Det 101, Archie reportedly joked, “Heavens no! What happened to the other 100?”

Archie was the first physician to join America’s new centralized intelligence organization. And, among the oldest to serve during World War II.

“Tip of the Spear” Deploys

When the U.S. entered the fight in Europe and the Pacific, Donovan envisioned the OSS serving as the nation’s chief wartime intelligence gatherer and operator of nontraditional warfare. In other words, the new organization would be the tip of the spear.

To defeat the enemy, the OSS required patriotic Americans who were independent thinkers of different ethnic backgrounds with professional expertise, linguistic skills, and cultural knowledge that would allow the spies to blend in overseas. Just like the OSS recruited European American officers for the European theater, the OSS turned to Asian Americans for mission-critical roles—often those that involved grave risk—in the Pacific theater.

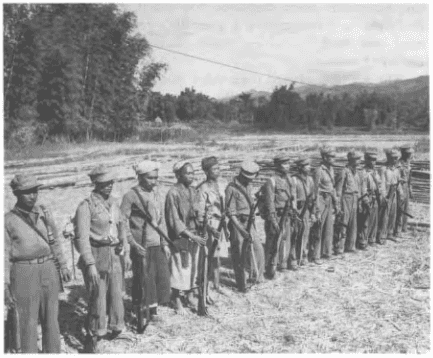

The original Det 101 team was composed of 20 officers and enlisted men, who trained for only a few weeks before being deployed to northeastern India. They arrived in Nazira, Assam on July 4, 1942. Their mission would be to orchestrate and support the Kachin people's guerilla warfare against the Japanese in the jungles of Burma—attacking Imperial Army forces, cutting off their supply columns, disrupting their communications, sabotaging their installations—all while providing intelligence to the Army, Navy, and Marines.

Squad of Kachin Rangers. [US Army photograph]

Archie, who was not accustomed to austere and rugged conditions with his previous professional background, was stationed in the China-Burma-India theater for two-and-a-half years as chief medical officer for Det 101. His primary responsibility was to care for the health of his 19 teammates. As the only trained medical officer for the first year, he was also in charge of providing medical support to the numerous guerilla fighter training camps spread across roughly 40-square miles.

In an official memo wrapping up his overseas assignment, Archie wrote: “During my tenure, three epidemics occurred in our area. Cholera broke out among the natives in October 1943; Smallpox in March and the first part of April 1944; and Malaria in June 1944. We successfully kept the epidemics from our camps through the enforcement of strict measures.”

Archie had other tasks as well, some of which were quite unexpected for a medical professional. These were dangerous times, and Archie used his skills as a translator and instructed Kachin fighters in the use of small arms and in demolition tactics.

A Humble Hero and Consummate Professional

Archie’s OSS tour ended in 1944, and he left India on July 25, one day before his 40th birthday.

He told the local newspaper back at home, “In guerilla warfare, there is no second chance to make good. When approaching an unfriendly tribal chief, our men knew they had to win him to our side or die in a [Japanese] ambush.”

“Irrawaddy Ambush” [© Stuart Brown. 2010. Oil on Canvas] This painting from CIA’s Intelligence Art Collection, displayed at CIA Headquarters and featured in “The Art of Intelligence” publication, depicts one of Detachment 101’s many guerrilla operations staged to disrupt Japanese supply and reinforcement routes in Burma.

For his accomplishments and service that went above and beyond the call of duty, Eifler recommended Archie for the U.S. Armed Forces’ Legion of Merit medal, writing: “Despite the hardships of enemy action, distance between camps, terrain and weather conditions, Major Chun-Ming not only rendered required medical service to the personnel and agents assigned to the detachment, but also unselfishly devoted himself to the native population in the surrounding areas. His splendid achievements developed friendliness and goodwill which richly rewarded the American Government by favorably influencing the natives toward America and enlisting their valuable aid to our cause. Courageously and boldly he voluntarily participated in many errands of mercy into territory occupied by the enemy and natives of unknown affiliation.”

Archie resumed his medical practice in Honolulu after his time in the OSS and continued to serve as a U.S. Army reservist, retiring as Lieutenant Colonel. He died on January 26, 1973.

Medical Professionals Supporting the Mission

To learn more, read “The Fighting Doctors of the Office of Strategic Services,” an article about the pivotal role that medically trained officers played in U.S. intelligence history.

The wartime doctors and nurses of yesteryear paved the way for the medical professionals today in the Center for Global Health Services, who advance the Agency’s mission at home and around the world. Some of the current jobs at CIA for medical providers include: