It is impossible to underestimate the historical significance of the 1936 Summer Olympics. Hosted in Berlin, Germany, the Games of the XI Olympiad, as it is officially known, would prove to be an exciting athletic spectacle, one that was ominously underscored by a worsening international political climate. Although it was not known at the time, the 1936 Olympic Games would be the final one for the next 12 years, owing to the outbreak of World War II.

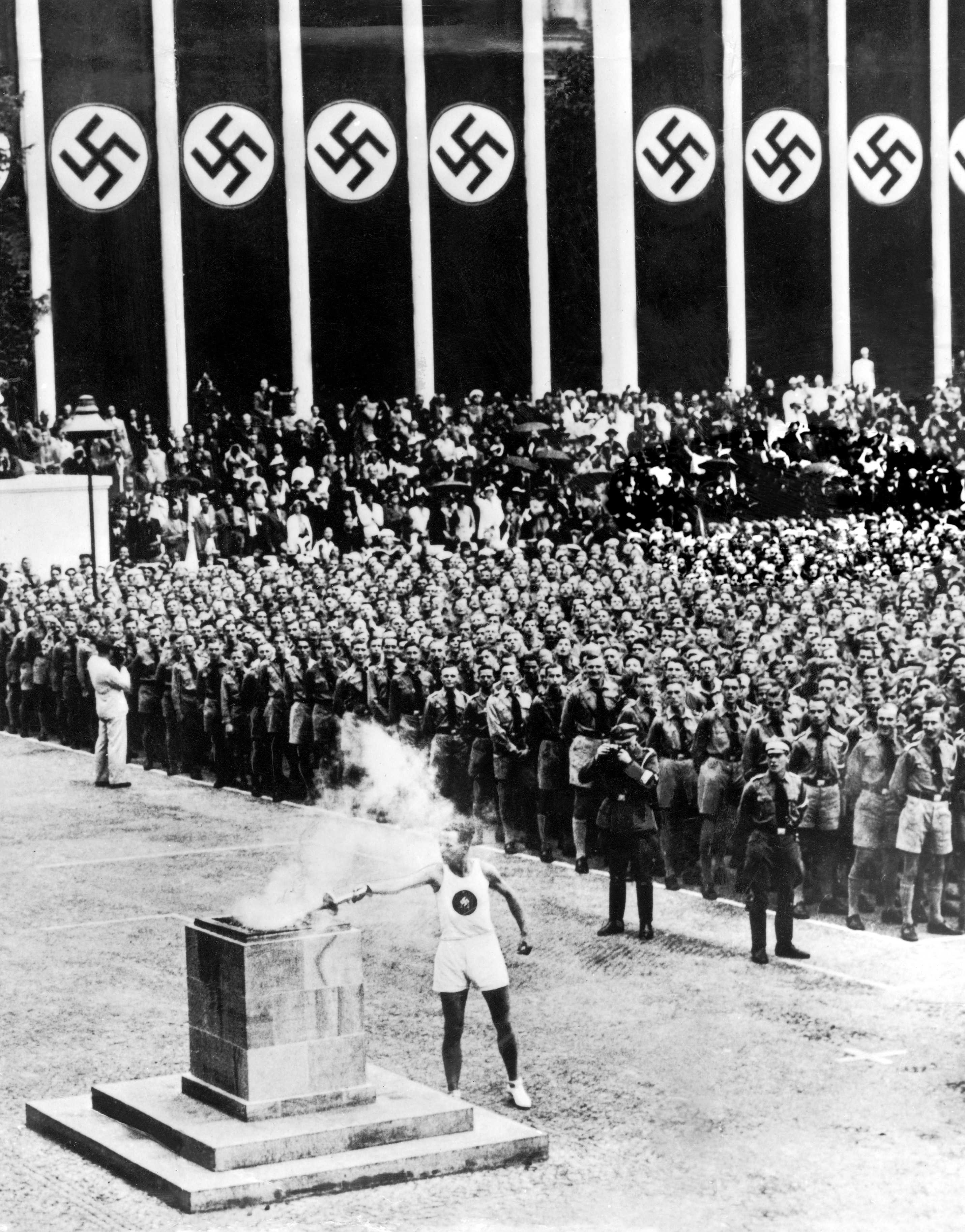

A German runner lights the Olympic torch at the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin. 1936 was the first Olympic Games to introduce the Olympic torch relay, a ceremonial relay from Olympia, Greece to the site of the Olympic Games. It is a tradition that remains today.

In many ways, the 1936 Olympic Games would become a historical precursor to our modern Olympics. It was the first televised Olympic Games, reaching an audience of nearly 150,000 remote spectators. It would also be the first Olympics to introduce the Olympic Torch relay, a ceremonial relay of the torch from Olympia, Greece (the site of the first Olympiad) to Berlin. It would become a tradition that is still in place today.

Athletically, the world saw the rise of U.S. track-and-field star James “Jesse” Owens, whose four Gold medals would earn him international acclaim and cement him in history as an athletic giant. A fitting victory that would have the welcome side-effect of subverting then Reich Chancellor Adolf Hitler’s ultimate goal: to project the primacy of the Aryan race and the strength of the Nazi regime. This would also be the first Olympic Games to incorporate Basketball as an Olympic sport, with the United States walking away with the sport’s first-ever gold medal.

But that is not the story we’re here to tell. No, our story starts a few thousand miles away, at a swimming pool in Boston at a little school called Harvard University.

Berlin or Bust

Charles Hutter, Jr. was a standout on the Harvard swimming team, a force in the water who would, the team hoped, finally lead Harvard to victory over their dominating Ivy League competitor, Yale. According to The Harvard Crimson archives, the Illinois native shattered the Harvard 220-yard freestyle record in his first ever race in varsity competition, beating the record by two full seconds. Hutter also anchored the team’s 200-yard relay team in that same competition, breaking yet another Harvard record by nearly 1.5 seconds. Alas, the newcomer’s prowess in the pool wouldn’t be enough to edge-out his Yale competitors in the 1935 season; that would have to wait a little while. Hutter had grander ambitions in mind.

The new year brought with it a new opportunity: the chance to prove himself against the best for the chance at an Olympic medal at the 1936 Olympics in Berlin, Germany. The road to Germany, as it turned out, would start just around the corner in Providence, Rhode Island. It was there, a month before the Games were scheduled to begin, that the country’s best young swimmers met at the Olympic Trials for a chance to join the Berlin-bound, 28-person roster. Hutter found himself up against some of the sport’s greatest competitors, including Jack Medica, Peter Fick, and Ralph Flanagan, to name a few.

The Harvard swimmer performed exceptionally in a field of fierce competitors, winning his opening heat and placing second in his semi-final heat. His performance earned him a lane in the final, where he placed fifth and, in doing so, punched his ticket to Berlin, becoming the first Harvard swimmer to ever make it to the Olympics.

Clash of the Titans

The U.S. Men’s 4 x 200 freestyle relay team, of which Charles was a member, consisted of six swimmers aged 17 – 20 years old. Their names were: Ralph Flanagan, John Macionis, Paul Wolfe, Jack Medica, Ralph Gilman, and Charles Hutter. Although only four were permitted to compete in any given event, six were allowed to travel, giving the team two alternates in the event of illness of injury.

Eighteen countries fielded teams in the event, but in the eyes of the spectators, only two mattered. As with most men’s competitive swimming events in the 1930s, the competition was always between Japan and the United States. In the first semi-final, Charles, Ralph, Jack, and Paul cruised to an easy victory over teams from Hungary, Great Britain, Denmark, Austria, Luxemburg, and Poland.

Swimmer on the Japanese Men’s Swim team at the 1936 Olympics

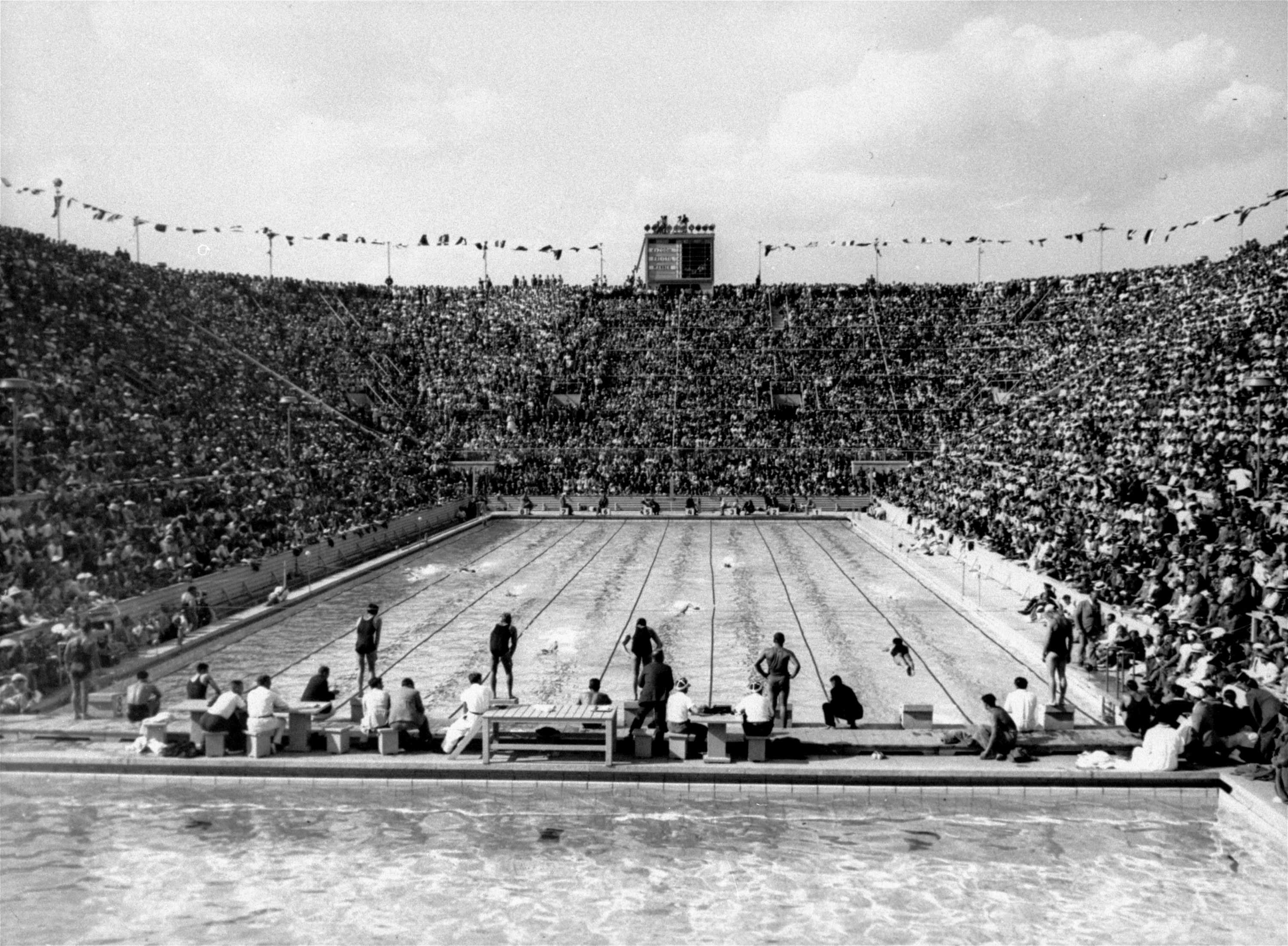

The next day’s final would pit the U.S. against Japan, and although Charles was picked to swim on the semi-final squad, he did not swim in the final. Teammates Ralph, John, Paul, and Jack swam to a respectable second place finish, behind a world-record-breaking swim from the Japanese relay team. Under 1936 Olympic rules, Hutter – as an alternate in the final race – did not receive a silver medal.

The final of the Men’s 4×200 Freestyle relay at the 1936 Olympics.

The Hero of Harvard

Following his team’s silver medal finish in Berlin, Hutter returned to Boston where he swam two more seasons with Harvard, setting Harvard records at four freestyle distances, three of which held for nearly two decades. It was in one of those record-setting competitions in 1937 that the Crimson finally put an end to Yale’s historic undefeated streak.

In 1938, Hutter captained an undefeated Harvard swim team to the school’s longest win streak in team history, 23 meets, and to the Eastern League title. He would graduate later that year, having left an indelible mark on the Harvard swim program. In 1971, Harvard recognized his achievements by inducting him into that year’s Hall of Fame class.

The Daring Doctor

Following his illustrious undergraduate career, Charles went into the medical field, specifically as a physician in the U.S. military. Records show that Lt. Col. Hutter, MC (Medical Corps), reported for duty at the American Medical Association in Chicago, Illinois in October 1940 for a two-year tour from the Office of The Surgeon General. Following this assignment, Lt. Col. Hutter served briefly in the U.S. Army Medical Department’s Medical Statistics Section. Although the specifics of the Lieutenant Colonel’s whereabouts between 1943, when he left his position with the Medical Statistics Section, are unclear, what is clear is that Hutter was assigned to the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), CIA’s World War II (WWII) predecessor.

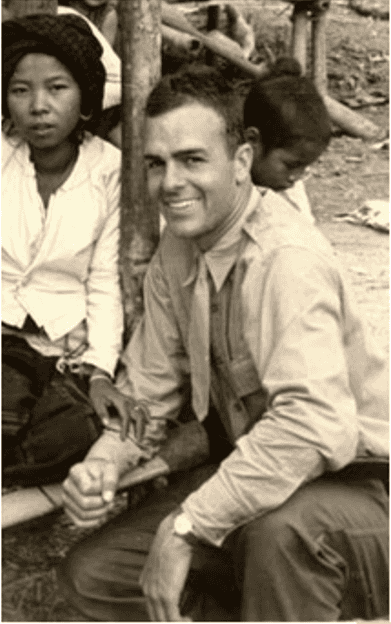

Dr. Charles Hutter, Jr. in Burma during his time with Detachment 101.

More specifically, Hutter cut his teeth with Detachment 101’s Burma contingent, the most accomplished OSS unit in the China-Burma-India Theater of WWII. From an original footprint of 25, the contingent grew its operational capacity to nearly 600 by the end of the war, recruiting nearly 11,000 native Kachin to fight the Japanese occupiers.

Dr. Charles Hutter arrived in Burma via parachute, touching down in the aftermath of a particularly costly battle during the final push against the Japanese. He arrived with much needed medical supplies and immediately went into emergency surgery, which he performed over a two-day period while a nearby airstrip was cleared to evacuate the wounded.

Hutter was a memorable figure in the Detachment, if not for his life-saving medical support then at least for his impeccable attire. Remembered by his fellow officers as “the only man in Burma wearing a tie,” Hutter never missed an opportunity to look his best, no matter the circumstances.

In 1945, Detachment 101 received the Presidential Distinguished Unit Citation from General Eisenhower, for its service in the 1945 offensive that liberated Rangoon. And in the official OSS War Report, which was compiled soon after the war, Detachment 101 was described as “the most spectacular OSS activity in the Far East.” Thanks, surely in no small part, to the work of Dr. Charles Hutter and others like him.

The work of Dr. Hutter and OSS physicians like him laid the foundation for today’s Center for Global Health Services, which continues in that same spirit of selfless service, bravery, and commitment to CIA, its mission, and its people.